George & Louisa Morris and son, William

We are first introduced to George and Louisa via this will, written by James M. Smith in February of 1850. George and Louisa are enslaved by James Smith and he is bequeathing them to his wife, Polly.

When James Smith died six years later, Polly too had already passed. In January 1854, Smith had added a codicil to his will, redistributing the property he originally intended for Polly to his children. This property included enslaved people, some of whom he mentions by name, but he does not specifically mention George or Louisa.

What happened to George, Louisa, and their young child? There is no official record of their sale in the Buncombe County Slave Deeds. Perhaps they had already begun working for one of Smith’s children, or they were moved in an informal, intrafamilial exchange.

James M. Smith, Last Will and Testament, February 9, 1850

“And I give and bequeath to my said wife as her absolute property forever the negro man George (the shoe maker) his wife Louisa her child William and future increase, and the girl Caroline (Lydia’s daughter) and her increase together with a good wagon and four horses and mules and harness her choice of my stock, six cows to be chosen by her sight beds and furniture of her choice of all on hands and provisions suitable for her of the value of eight hundred dollars.”

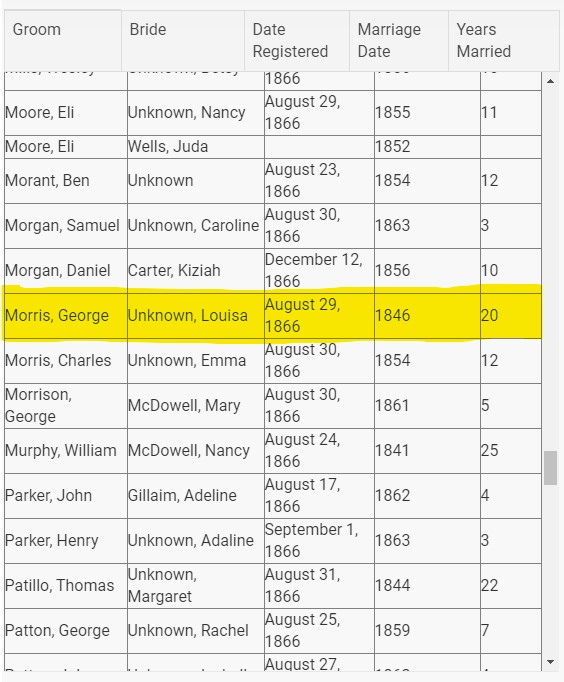

In 1866, former slaves in North Carolina were required to have their marriages ratified by County Clerks, as decreed by an act passed by the North Carolina Generally Assembly in the spring of that year. The Buncombe County Register of Deeds has transcribed these cohabitation records and made them publicly available.

In these records we can see that on August 29, 1866, George Morris and Louisa (unknown last name) had their marriage of 20 years ratified by the county. Their first names, and rough timelines, matched the information we found in James Smith’s 1850 will, meaning it was likely the same people, but possibly not. So, we kept looking into the public records.

Images Courtesy of U.S. Census, 1870

The Federal Census of 1870 was the first census to include African Americans as citizens and list them by name. In this page, from Buncombe County, we found a 63-year-old shoe maker by the name of George Morris, living with a 50-year-old housekeeper by the name of Louisa, and a 20-year-old laborer named William. We now have names, ages, family relationships, and George’s occupation all matching up with the details mentioned James M. Smiths last will and testament from 1850.

The 1870 census gives us quite a bit of information about the Morris family. The first thing we learn is that George is originally from Virginia, and that he owns land valued at $100(?). There are several people besides George, Louisa, and William living in the Morris household. Five of them appear to be George and Louisa’s children; Campbell Morris, a 15-year-old laborer, Lucy Morris, an 11-year-old student, Anna Morris, 8, Mary M. Morris, 5, and Alfred Morris, 2. There are two others, Dan Feemster, a 25-year-old shoemaker, and Manuel Williams, a 15-year-old farm laborer.

The two young men listed as part of the Morris household, Dan and Manuel, offer insight into the Morris family life. What is their connection to one another? Does Manuel, a “farm laborer” work for the Morris family on their property? Dan is listed as a “shoe maker,” the same occupation as George. Could he be an apprentice? Who are they making shoes for?

In the search to find out more about Dan Feemster, we came across another mention of him in the 1870 census, as a part of the George Thomas Spears household. George Spears was married to Jane Cordelia Smith, James Smith’s daughter, which presents a likely connection between Dan Feemster and the Morris family.

There is not any other definitive mention of Dan prior to, or after 1870. In the 1860 slave schedule, part of the U.S. Census pre-emancipation, George Thomas Spears lists ownership of a 16-year-old boy (along with many other people), which matches Dan Feemster’s age on the 1870 census.

The only other possible record of Dan Feemster is from an 1849 deed of sale of an 8-year-old boy named Daniel to Jacob Weaver, by Patton and Burgin. This doesn’t quite match up with Dan’s age in the census, but the births of enslaved people were commonly not documented, and ages were often estimated by people with no actual knowledge of the individual.

Perhaps George and Louisa Morris met Dan Feemster at George and Jane Smith’s estate, and perhaps they worked together there before slavery ended. Did George teach Dan his craft? Did they live together or just work together in 1870? What happened to Dan after 1870? Researching Dan Feemster hasn’t proven to be very illuminating about the Morris family, but it is an all too common instance of African American identities being discarded by the annals of history.

Looking into the life of Manuel Williams yields even less information than Dan. George Spears’ 1860 slave schedule does have an entry for a 6-year-old boy, which aligns with Manuel’s age on the 1870 census, but, like all of the nameless people accounted for on the 1860 slave schedule, we are left to merely speculate about their true identities until more primary documentation can be uncovered.

Images Courtesy of U.S. Census, 1870 and 1860.

Image Courtesy of Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

“Accuired of Jacob Weaver Three Hundred and twenty dollars in full of the purchase of a negro boy Daniel about eight years old which negro we warrant to be sound in body and free from all other lawful claims 13th. Oct. 1849. Patton & Burgin-“

The Morris family is listed again in the 1880 census. In this year the census notes the marital status of each adult, and each person’s relation to the head of household. Louisa is listed as the head of household, and we learn that sometime in the previous ten years, George has died and she is now widowed.

Image Courtesy of U.S. Census, 1880

We also confirm that all five Morris children listed in the 1870 census are her children. There is no mention of Dan Feemster of Manuel Williams, but there are three more children, listed as her nieces and nephew, living with her.

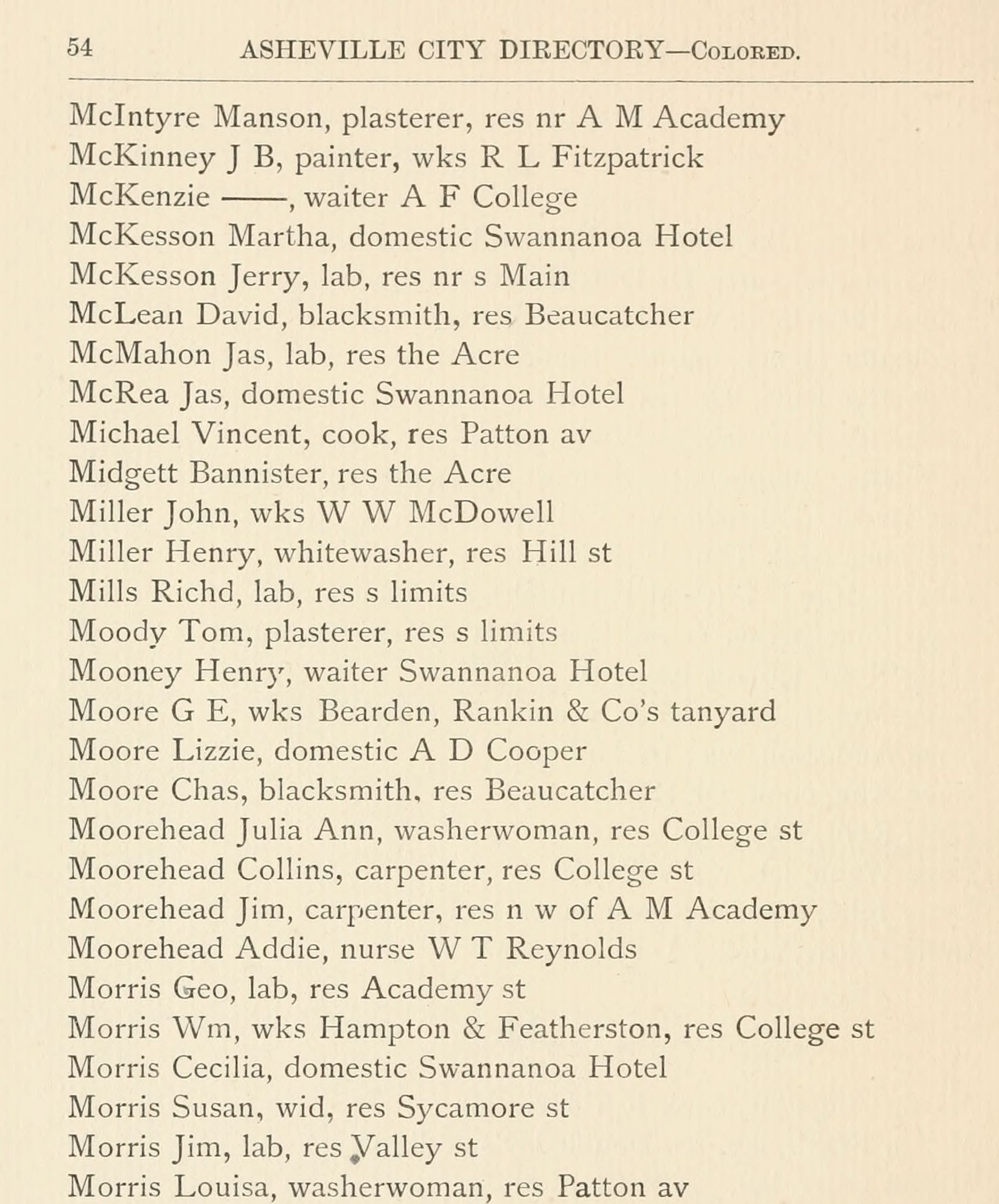

In the years 1883-1884, The Baughman Brothers published a city directory of Asheville. In the “Colored” section of the directory, there is a listing for Louisa Morris, which says she is a washerwoman, residing on Patton Avenue. There is also a listing for a William Morris, residing on College Street.

It seems we may have found a tangible place where the Morris family lived and worked, possibly from the time of their emancipation. The William Morris listed as residing on College Street may or may not be George and Louisa’s first child. If he had lived there in 1880, we could presume he would be listed as a separate household on the census. He could have moved in those few years since the census, or it could be a different William Morris.

This part of the deed reveals a lot about the Morris family. We now know the married names of all of Louisa’s children and can pursue all of the census records, deeds, and city directories to follow them and potentially their descendants. We found perhaps the most important part of this deed buried within the legalese and technical jargon that defined the boundaries of this lot.

Image Courtesy of the Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

In this section we learn that the acre of land sold to Benjamin Alexander Julius is the same plot of land purchased by George Morris. It also becomes evident why we were previously unable to locate this document, as this deed from 1889 indicates that he is called George Smith in this record, a public gesture indicating his previous enslavement by James M. Smith.

This is the original deed of sale for the land purchased by the Morris family after emancipation. It indicates that he bought the acre where he and Louisa raised their children for $150 from Jarvis and Anna N. Buxton. This deed locates the land on the (as of 1872) “south side of Haywood Road and on the west side of the street running south… beginning at the junction of the two streets.”

This map, published by the Burleigh Lithographing Establishment of Troy, N.Y. shows an aerial view of the City of Asheville in 1891, just two years after Louisa Morris and her children sold their property to Benjamin Alexander Julius. Using the description found in the 1889 deed, “On the south side of the New Haywood Road now called Patton Avenue, and on the west side of the street running south…, now called French Broad Avenue. Beginning at the junction of the two streets,” we can see a cleared parcel of land, surrounded by trees and homes. There is a one story house, situated close to the street on the corner of Patton Avenue and South French Broad. In all likelihood, his is the property purchased by George Morris in 1872, where he worked with Dan Feemster and Manuel Williams, and where he and Louisa raised their six children.

“Bird’s-eye View of the City of Asheville, N.C.,” 1891, courtesy of the North Carolina Room at Pack Library.

Written and researched by Emily Cadmus, WNCHA intern, Fall 2020